Workshop XXI, Karen Pinkus, 15 March 2021

In her speculative and wide-ranging presentation, professor of Italian and comparative literature Karen Pinkus considers the possibility of post-oil narratives – what might these look like and how would they resemble “oil” narratives or other narratives of our recent past and present. She begins by introducing two oil narratives: Oil! (1926-27) by Upton Sinclair and Petrolio (1992) by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Perhaps if we could identify elements that characterize oil narratives, this could help us to imagine post-oil narratives, and thus the future.

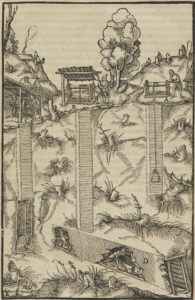

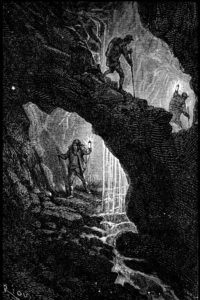

Karen Pinkus focuses in her current work on the period which marks the end of coal and the beginning of oil, and explores the relationship between surface and subsurface as well as the subterranean and narrative. The images of underground tunnels contained in Georgius Agricola’s De re metallica (1556), the Renaissance’s most important book on mining, are a meaningful referent here. Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), with its exploration of the Earth’s subsurface, also deserves a profounder reading. A key question guiding Pinkus’ research is: How do we know what is underground and how do we tell a story about it? She also draws our attention to the visual model of the cutaway, which draws on conventions of linear perspective.

Another key referent for her is literary scholar Peter Brooks’ Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative (1984). In this book, which focuses on the nineteenth-century narrative tradition, Brooks claims that plots are both organising and intentional structures. He draws on psychoanalysis, from which he borrows a model for approaching the text as a “system of internal energies and tensions, compulsions, resistances, and desires” (Brooks, p.xiv). Pinkus finds this psychoanalytic approach useful to tie narrative to the story of human life and desire. She sees a connection between Brooks and coal and speculates that one may also perhaps link it with oil and post-oil.

Duria Antiquior, a more ancient Dorset, a watercolour painted in 1830 by the English geologist Henry De la Beche, has played an important role in thinking the Earth. Duria Antiquior was the first pictorial representation of a scene of prehistoric life based on evidence from fossil reconstructions. De la Beche’s painting, an interesting imagined representation, offers a split-level view which shows action both above and below the surface of the water. This painting can potentially open up a reflection about how we imagine the Earth, stirring thinking about the subsurface and its relationship with time. Narrative gives us a timeline which affects the way we read.

Looking into possible futures, Pinkus asks whether scenario-planning is itself a form of narrative. She shows us a future scenario published by Shell. This graphic representation of the future is not very different from the present, as Shell here has merely replaced oil with electricity, leaving structures intact. However, Pinkus has not found a truly “speculative” narrative about the future yet. For her the presentation of a post-apocalyptic world in climate-change science fiction (cli-fi) is also rather unimaginative, though she acknowledges there are exceptions, such as the biopunk novel The Windup Girl (2009) by American writer Paolo Bacigalupi. However, cli-fi has not actually offered the language or linguistic form to engage with the chaos that climate change has generated.

Finally, what kinds of fantasies allow us to designate the “after”? The issue of a post-oil future should be separated from climate change. She in fact leaves climate change aside in her attempt to narrativise oil, a substance we only get to see after it reaches the surface or through imagined cutaways. What would a post-oil world look like?

narrative I Upton Sinclair I Pier Paolo Pasolini I end of coal I underground I cutaway I psychoanalysis I scenario-planning I cli-fi