Workshop XXII, Andrei Molodkin, 23 March 2021

France-based Russian artist Andrei Molodkin begins his presentation about his work with crude oil by telling us about his army days. Whilst studying he also served in the Soviet Army, convoying missiles through Siberia. In the freezing temperatures Molodkin would rub oil over his body to provide the warmth to keep himself alive. Covered in oil, the soldiers would often stop along their dangerous route, with villagers taking pity on the men and providing them with food. Oil became his source of survival. This military experience is an important referent for Molodkin’s work with oil.

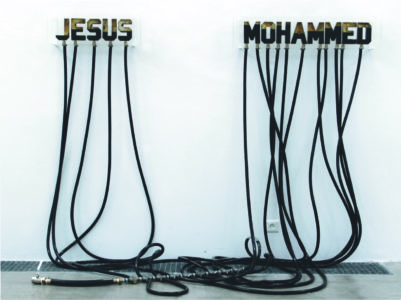

“Where does oil come from” and “What does it represent?” are some of the key questions guiding his formal work with the political material. Molodkin tells us that oil from each region has its own properties; the colour, smell and taste differ. Making symbolic connections between politics and culture, Molodkin creates hollowed shapes of classical structures and sculptures, through which crude oil is then pumped by way of a complex network of tubes and hoses, like the circulatory system of a human-being. In the exhibition CRUDE (November 2011 to February 201) at the Station Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston, Texas, for example, oil is pumped through a replica of the dismembered head and torch of the Statue of Liberty, and also through direct words such as “Justice” and “Revolution”.

Andrei Molodkin describes oil as a political language, through which countries communicate with each other, and also as a generator of geopolitical conflict, pointedly summed up by the US-American phrase “our oil is in your soil”. After working with oil for a while and understanding its political charge, he felt compelled to explore the idea of “blood for oil and oil for blood” around 2007, in exhibitions such as G8 at Kashya Hildebrand in Zurich, or Direct from the Pipe at ANNE+ Art Projects, Ivry sur Seine. This installation consists of two acrylic sculptures of Jesus, with oil pumped into one of them and blood into the other. The enlarged images of the two sculptures are projected as a live-stream onto the wall behind.

Molodkin’s installation Le Rouge et le Noir at the Russian Pavilion at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009, and in particular use of the blood of Russian soldiers in Chechnya was seen as controversial by the organizers, who removed the contextual information provided for viewers and restricted press from communicating with the artist. Under communism there was an official culture and an underground culture, a distinction that still holds. Just last year, his installation The White House Filled With the Blood of U.S. Citizens (2020) in Washington DC was due to be exhibited in the lead up to the Presidential Inauguration. Due to escalating violence in the city the artwork was deemed too dangerous to exhibit and was pulled from its intended location, finding its place on the streets instead.

Oil is a political, dirty material. It propels life, but is also dangerous. This is why to see it in the clean white walls of a gallery is such a powerful experience for the public.

conflict I soldiers I blood I ideology I religion I Chechnya I Venice Biennale I underground I censorship